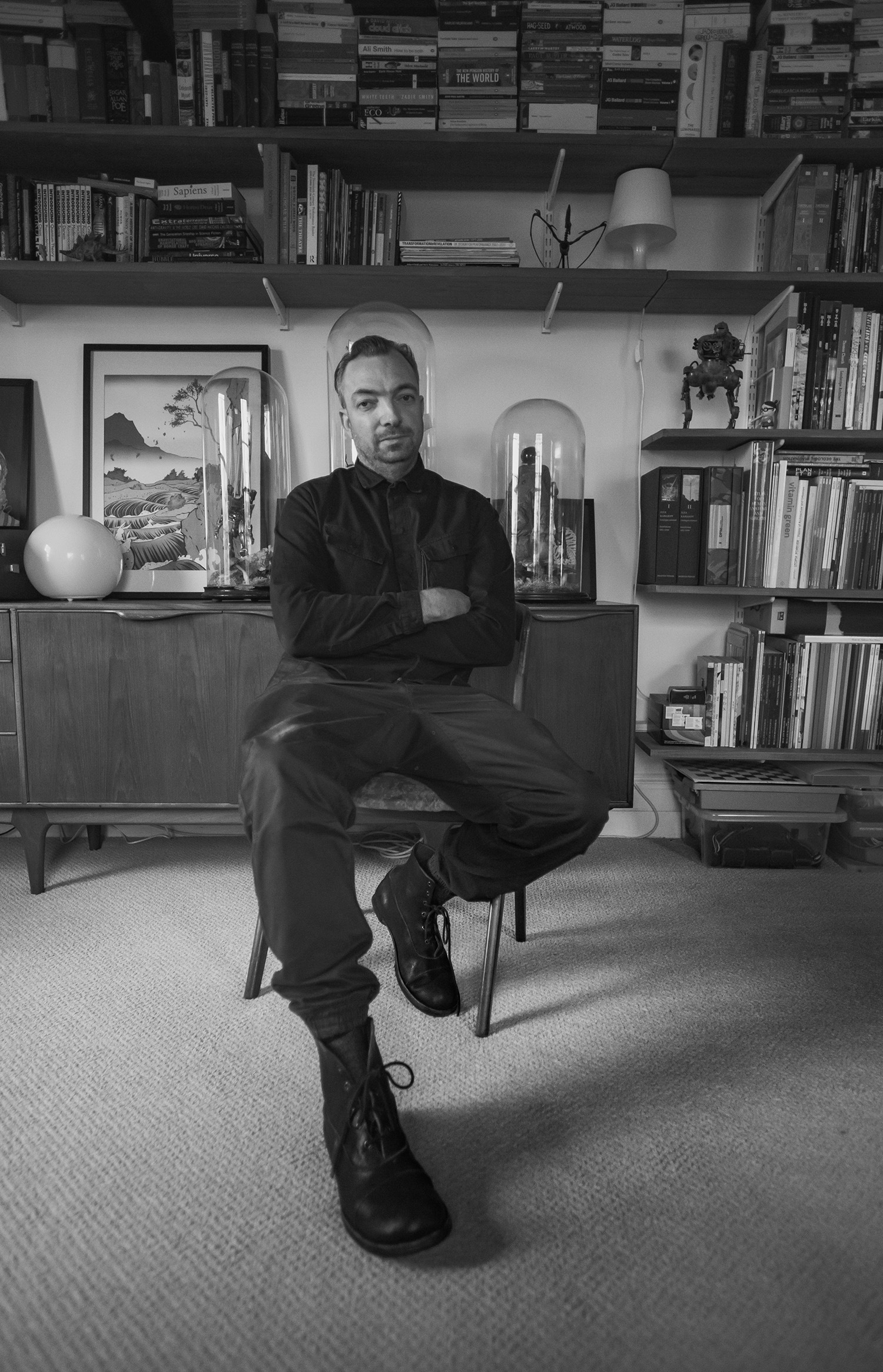

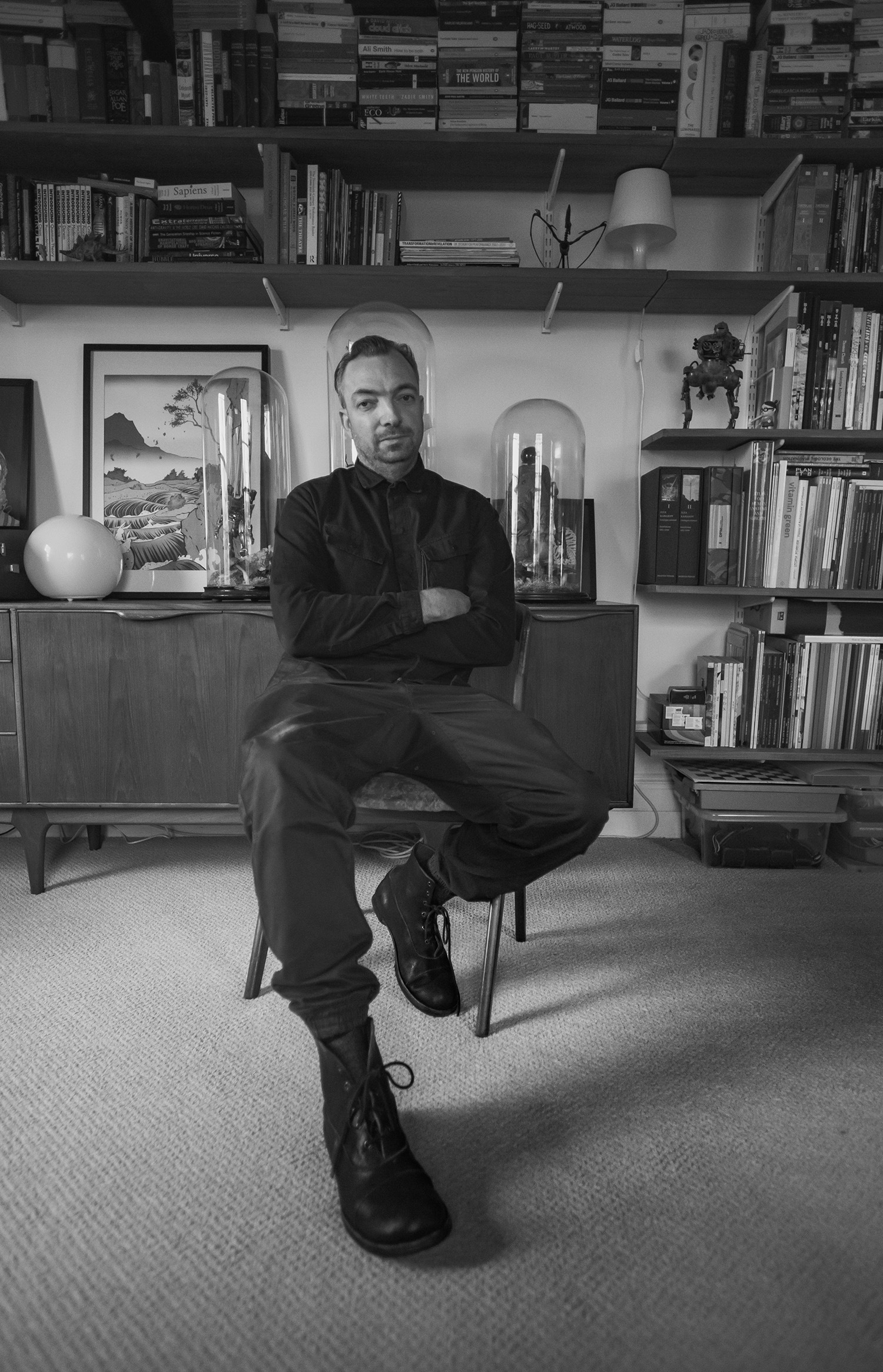

Liam Young

I'm looking at two stuffed and mounted robotic creatures under bell jars in Liam Young's Hackney apartment. One is a carbon dioxide scrubber—a model of an artificial mobile tree, meant to roam the Earth in flocks and suck CO2 out of the air to produce more oxygen. The other is a robotic firefly, which detects sections of the sky blocked out by pollution and coalesces around wireless signals in order to create an artificial aurora for humankind's aesthetic viewing pleasure.

| Liam Young | Speculative architect, designer, film director |

| Web: tomorrowsthoughtstoday.com unknownfieldsdivision.com | Social Media: |

Both these fictional prototypes are part of Young's 2012 interdisciplinary art project, called Specimens of Unnatural History and consisting a collection of augmented biotech creatures and short stories. They each reflect on the gradual convergence of nature and technology and future ecological collapse.

"I tell stories about the architectural and urban implications of new technologies, so we speculate about the ways that these technologies are changing our lives, and changing our world," says the London-based architect, designer and film director. "We use the tools of film, fiction and performance in order to visualize these stories, and present them in mediums that wider audiences can relate to. For the most part, my work involves traveling around the world, seeking out the weak signals of possible futures, exaggerating them or extrapolating them into future scenarios."

Also running London-based research studio Unknown Fields Division with artist, architect and writer Kate Davis, he brings artists, creatives, and researchers together to track down these Gibsonian futures of structural inequality, as well as the ecological effects of outsourcing production. It's manifesto reads as follows:

Here we are both visionaries and reporters, part documentarians and part science fiction soothsayers, as the otherworldly sites we encounter afford us a distanced viewpoint from which to survey the consequences of emerging environmental and technological scenarios.

One Unknown Fields Division project, 'Rare Earthenware', retraces rare earth elements widely used in smartphones and high-end electronics to their origin at Lake Baotou in Inner Mongolia—a site that turned radioactive from the byproducts of mining these chemical elements. Their trip was documented and presented in a film directed by Toby Smith, while ceramicist and multi-disciplinary artist Kevin Callaghan used the mud to craft a set of three Ming Dynasty vases. Each is sized in relation to the amount of waste created in the production of three technological devices: a smartphone, a laptop, and an electric car battery.

"This project is trying to speculate on a new material aesthetic for the technologies that are born of the earth," Young says of these objects mimicking 15th century Imperial porcelain, one of the first high value luxury commodities traded internationally. "It's trying to reflect on the presentation of new technologies as this seamless, super clean, refined and elegant object, which is actually a form of camouflage to disguise its real origins in the ground of the Earth."

Young was trained as a traditional architect, working for iconic London-based architect Zaha Hadid for two years after graduating. But he soon realized that instead of building monumental statements of capital, he'd rather work with mediums more relevant to the wider public. "[We] architects are very famous to a very, very small group of people," says Young. "We're very good at talking in dark lecture halls to people that already agree with us. We're very good at publishing books that no one reads journals that no one buys. We've created an entire culture and community around validating our own irrelevance and I was sick of screaming into the void."

Young left the late-Hadid's office along with his architecture practice and started experimenting with fiction. "Ever since we can sit up, we are put in front of the TV to watch stories, or later we fall asleep reading a novel. There's a global literacy of stories and fictions, and it seems really potent as a way of connecting people to important ideas." Young's work gradually evolved from experimenting with narrative-based art projects to storytelling and film work. "I'm much more interested in data dramatization, as opposed to data visualization because we can use fiction as a way of making the public emotionally complicit in some of these ideas."

One clear attempt at this kind of persuasion is present in Young's use of film and special effects from his Los Angeles studio. "Every film that I make—unlike traditional forms of film practice in Hollywood—doesn't start with a script, 'doesn't start with a series of characters and their motivation," he explains, applying his findings from the Unknown Fields Division research trips to this popular mode of visual storytelling. "It starts with the construction and creation of an imaginary, speculative world. Then you populate that world with characters, people, objects and a narrative. We look at what is the best kind of character, the best storyline in order to convey that world in the most powerful way to audiences."

'Where the City Can't See' is a film shot entirely using lidar scanners—the optical technologies that autonomous vehicles use to navigate. It's set in an automated city: future Detroit. The audience explores its streets from the perspective of a driverless taxi across the course of one night. The cab encounters a group of young factory workers who labor on production lines by day and go to illegal raves by night. The narrative speculates on ways youth culture might resist machine vision and surveillance technologies.

Young and his team also designed and developed a series of camouflage costumes these ravers would wear. They would reflect the laser light and create glitches and distortions in the dataset of tracking algorithms. "Because we were designing that world, it was important to us that these textiles actually worked," he says. "We've exhibited these costumes and these textiles as physical pieces, and we've put these props together with the film as a way of conveying the nature of that world."

Young and his team also worked with a choreographer to create dance movements for the rave scenes that would distort the forms and silhouettes of its dancers, thus interfering with tracking and tricking surveillance algorithms. The work is a comment on the effects of Google Maps, CCTV surveillance, and computer vision and urban management systems on our cities but these future worlds are neither utopic, nor dystopic. They're not science fiction. These are nuanced scenarios exploring the consequences of emerging technologies in a wider cultural context. "I think any speculation that is valuable operates in that same way," he explains. "It exists between the real and the imagined and presents an image of the world that is complex and difficult."

New technologies often take center stage in Young's films because of their role in reshaping our culture. Their impact is inescapable. "The rhetoric of these technologies is based around human-centered design, or user-centered design but they're really talking about customer-centered design," Young says, referring to the drones, self-driving cars and artificial intelligence steadily entering the market. "A technology is going to appear, not because it's valuable, or useful, or productive but because it can be sold."

According to Young, it's our generation's responsibility to unpick the politics that produce these developments and look for alternative ways of imagining them. "I think all the technologies that we engage within our work have come at us at a faster pace than our ideological capacity to understand what they mean. What we try and do with our work is prototype the cultural implications of these technologies, so that we can become more informed consumers of these things, rather than just standing in line waiting for the next iPhone to be released."

That said, Young's overarching focus is not just on emerging technologies but contemporary culture. His next project explores automation and its consequences for both labor and personal identity in future societies. It asks, when we so often define ourselves by the work we perform, what does it mean when the nature of that work shifts?

A third medium Young has developed through a combination of his documentary-based and more fictional work is his so-called 'live cinema', which is a way of presenting his future worlds in a more immediate and personal way. "I like the format. For me, it's fun to do as a performer but it's also much more engaging than a shitty PowerPoint. I get invited to do them at music festivals, at art festivals, in an academic context, in a whole range of different public forms that, if I was just a lecturer, I wouldn't have access to."

Young does a new lecture performance for every movie he releases. 'Where the City Can't See' highlights his work on smart city technologies, starting with Young asking his audience to sit together in the back seat of a driverless taxi From here, they explore this world in a cinematic collage of existing, emerging and speculative near-future technologies on a screen behind him. The projection and Young's accompanying narration is a journey from the urban outskirts, where all these technologies begin their lives, into the city center where we see the strange augmented creatures the citizens have become.

Right now, Young is working on the ambitious task of designing a new metropolis called 'Planet City' for the entire population of Earth: What if it could be as densely populated as Kowloon Walled City used to be north of Hong Kong Island. According to his research, all of the world's human inhabitants could fit into an area the size of Palestine, or half the size of the Greater Tokyo Area. This would mean that the rest of the planet could be returned to a planetary-scale wilderness. "It's a provocation, a speculation for how we might live in extreme density, a visualization of the extreme lengths that we might have to go to in order to repair and remediate the planet that we thoroughly destroyed."

Young's practice presents us with stories about who we are and poses questions about who we want to become. He uses the phrase Trojan Horses to describe the way he embeds these ideas in the mediums of popular culture. "We're in a post-truth, fake news world, where the person with the most pervasive fiction wins. And in that context, we need to get really good at putting the right kind of fiction into the world. "

Written by Andrea Kelemen