Frictionless time tracking software for teams

Give your team a time tracker they’ll love, and help your managers make profitable project decisions with meaningful time data insights.

Flexible time tracking tool for your business needs

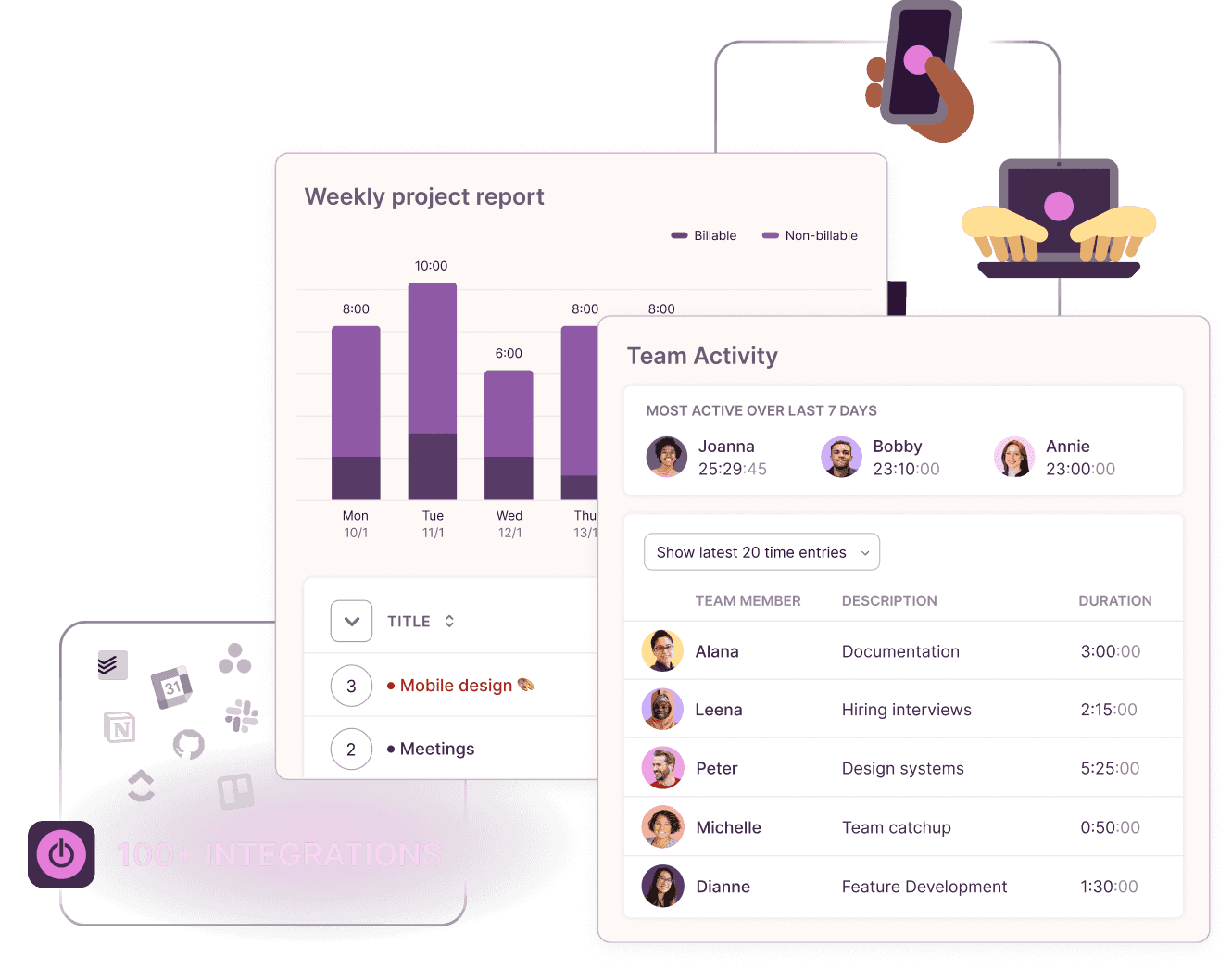

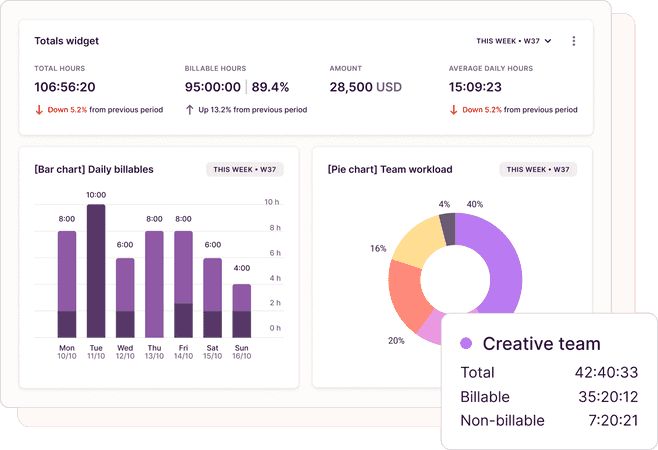

Insightful time reporting software

Know exactly how much time your team spends on tasks

Say goodbye to inaccurate weekly timesheets and get a handle on your team's exact billable and non-billable hours.

More about time reporting

“Time management software that helps improve metrics and estimates”

Marie, Project Coordinator

micromanaging my employees?

No, we do not. At Toggl, we see time as an opportunity.

An opportunity to convert time tracked into actionable insights that boost productivity, increase efficiency and balance team workloads. So you can drive profitability and growth while prioritising your team's trust and well-being.

Companies that use Toggl Track see:

40+ hours saved monthly

at Perception Engineering with one-click time tracking and reporting

100% time tracking adoption

with easy, non-intrusive time reporting at software consultancy Newlogic

20% increase in profitability

by accurately tracking billable work hours at Sweat+Co PR agency

Want better insights on how your team is spending their time?

No credit card required

Free 30-day trial for all features

Cancel anytime

The non-intrusive time tracker for self-driven teams

Onboarding a large team? We’d love to show you around.

Teams of 15+ are eligible for a custom demo to see how Toggl Track works at scale.

Time tracking apps for all devices and platforms

GDPR-compliant. Your data is safe with us.

Top-rated customer support with 3-hour response time

99% uptime for your peace of mind

Why 120,000+ users started tracking time with Toggl Track in the last 30 days

Easy for both team members and managers

So nobody views time tracking or reporting as a dreaded chore.

“Versatile and easy even if you’ve never used time tracking software before”

Kathleen, Service Area Manager

Better than the best

And we're 100% against employee surveillance — use a time tracker that gets a "yes" from every employee.

“Chose Toggl Track after trialing 20+ similar time tracking tools”

Andy, Software Consultant

Top-rated support

With a dedicated customer success manager for enterprise teams.

“Regular updates ensure that any bugs are caught quickly and customer support responds within a day; these features make using Toggl Track a breeze.”

Trevor, Senior Project Leader

Get your team going, faster

Low learning curve with no training necessary.

“No complicated setup or unnecessary bells & whistles!”

Renee, Senior HR Coordinator

Track time anywhere

From web to integrations to mobile, there’s a time tracking app for everyone!

“Easy to use time tracking app for desktop and mobile”

Rachel, Small business

Small team and no budget? We have you covered

“The best free time tracking app”

Learning to use Toggl is a breeze, because it's highly intuitive and simple. It ushers you along quickly so that you get back to work right away and start tracking your time immediately. The free plan is generous and could be more than adequate for solo workers or even small groups of up to five people with light needs.

It's not one of those apps where you need to spend half a day figuring out how to actually use it: sessions can be started as they happen or added later, and once the app has got a feel for your schedule and how you work, it'll even make suggestions about what you want to track next.

With Toggl Track, you can track your time right away and view your tracked time entries, and worry about the details later. It also has a generous free tier of service that gives you access to all its apps (Android, iOS, Windows, macOS, Linux, Web, and browser extensions).

Discover how time tracking can help you build a better business with higher profits and happy teams

Toggl Track's Free plan is free forever. Our Premium plan comes with a free, 30-day trial. No credit card required to get started.